Fireworks: Kenneth Anger and My Proud Faggot Past

Exploring the mystic, subcultural background noise of a gay bohemian life

Once upon a time, I was a gay witch. My partner, “W,” said he’d manifested me with a spell. He had lit the incense on his alter. He had burned candles. He had brandished his athamé and said the words that would draw me to him.

Drawn I was: to his bed, his strange chosen family and his coven.

Our life was steeped in marijuana, incense, Stevie Nicks and Madonna. We lived on the top floor of a strange old house in southern Oregon that was the architectural equivalent of conjoined twins. It was actually two houses joined at the kitchen, never to be separated. There was a broad, covered porch and a view of the surrounding fawn-colored hills which would burst into flame every summer.

The rooms below us were filled with friends. Writers, tabla players, therapists in training, astrologists. We celebrated Beltane and Samhain and the seasonal solstices. We had a garden of medicinal herbs and animals we regarded as familiars.

I was very much in love with W. He’d grown up gay in the same Colorado wasteland where I’d grown up bisexual. He was also 8-years my senior and had a harder go of it than me.

Those hard times had driven his intellectual curiosity and he carried with him a collected homosexual cultural knowledge that I’d never been exposed to. After all, I was young — just 21 when we became lovers who would later become partners.

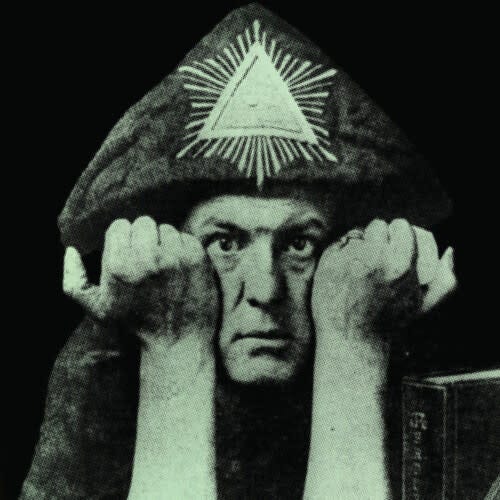

W introduced me to wonders that would be woven into my character and forever alter the way I view the world. He taught me about Alistair Crowley and Starhawk. He introduced me to Tom of Finland and the Bronski Beat. He taught me about drag and gay dance clubs and how to truly critique pop-culture spectacles like the Oscars.

Eventually he’d teach me about living with HIV, monitoring T-cells, full-blown AIDS and the resiliency necessary for living life on the fringes. But all of that came later. My initial education was all art and magic, and the symbolic headmaster of that education was Kenneth Anger.

Anger was an independent art-house filmmaker and author. He was also an adherent of Crowleys’ Thelema occult religion. Over his long and influential career, he is credited for inventing the music video and spawning dozens of Hollywood urban legends. He wore his homosexuality on his sleeve long before it was legalized in the United States and made friends with sexologist Alfred Kinsey. He worked with a pre-Manson-murder Bobby Beausoleil and a pre-Altamont-murder Mick Jagger (who would scored one of his films).

My experience of that time certainly held an Anger-esque, magik, sexual vibe. And two of his works became part of a set of foundational personal holy texts1 upon which I lived.

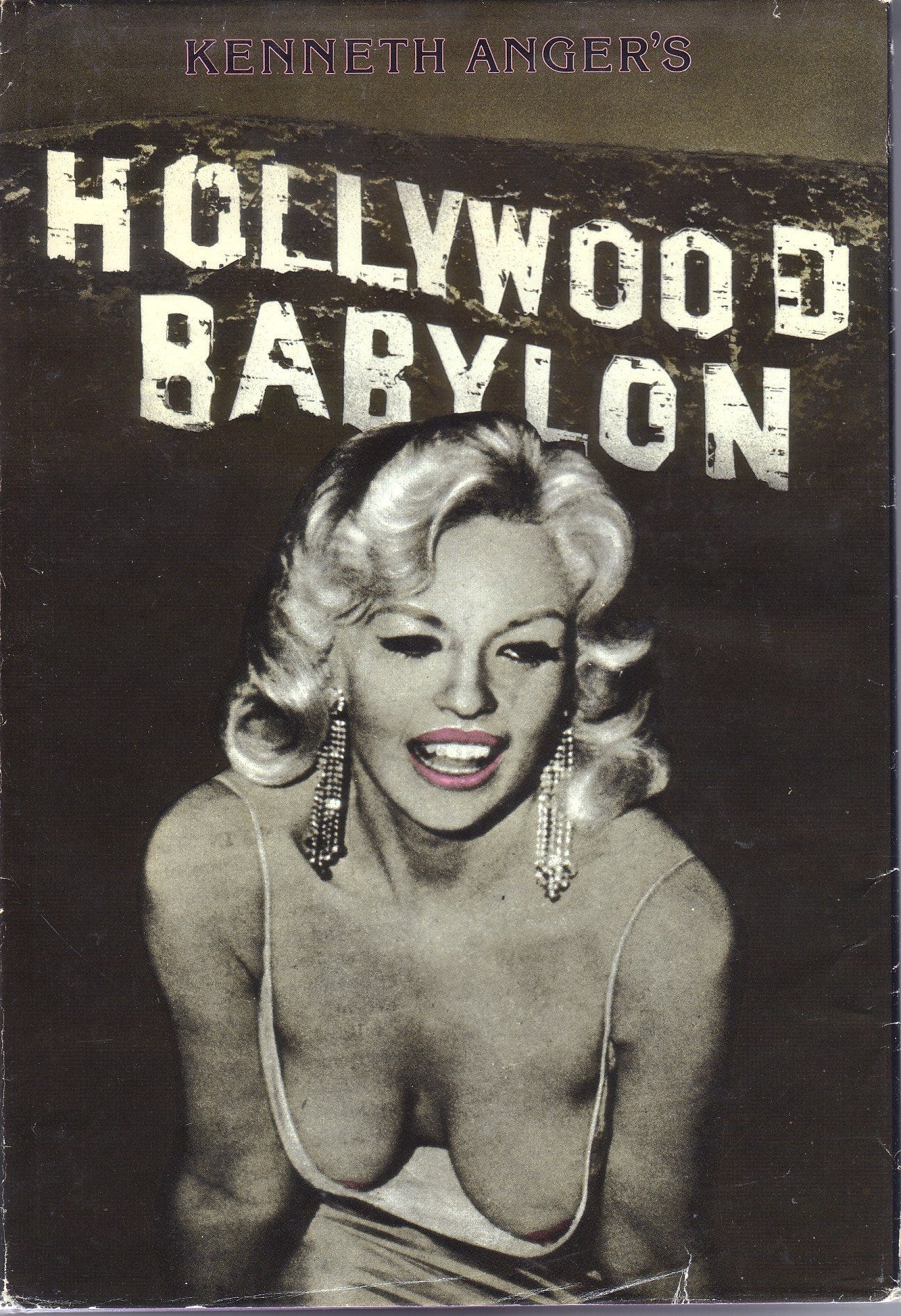

The first of those texts by Anger was Hollywood Babylon. When the book dropped into my hands I was well ensconced in my witchy, bitchy life. Thus, the filthy tome of dubious gossip from Hollywood’s golden era became a constant reference. I was working as a live-in caregiver at a group-home for developmentally disabled adults three days out of every week. I would spend my ample downtime pouring over Anger’s apocryphal tales of power lust and murder.

Anger makes some wild claims (the vast majority of which are untrue) in Babylon. He suggests silent film actress Clara Bow fucked the entire USC football team. He writes that Fatty Arbuckle killed starlet Virginia Rappe under his massive weight during a sexual assault that started by cannonballing onto the bed. And he covers reports of a pre-fame Clark Gable giving blow-jobs to further his career.

Among these stories are photos that include a nude Joan Crawford, raging parties of Hollywood royalty and a Black Dahlia murder scene.

Hollywood Babylon was my trash-culture primer. It was deeply exploitive and shocking while also being wildly camp. Owning the book meant you were part of a community connected to the seamy and unusual. It held a kind of dangerous subcultural cache, like a gay version of the Anarchists Cookbook. But instead of being loaded with instructions to make bombs, it was loaded with queer-centric sexual gossip to blow minds.

The second holy text by Anger was the underground short-film Fireworks, made in 1947. I am completely unable to recall how I got my hands on a copy of the movie. And I am equally unable to recall just where I watched the flick. Never-the-less its stark images were burned into my heart like a brand.

The loose narrative through-line of Fireworks follows a young man who wakes from a dream to seek a light for his cigarette. On his journey he is beaten up by a member of the Navy, then pursued and further beaten by a whole gang of chain-wielding seamen. They open his chest with a smashed bottle to discover a compass within. Finally, our hero, wearing a Christmas tree as a head dress, returns home and wakes next to a man whose face is obscured by a corona of light.

Fireworks is a startling vision for it’s time. The high contrast black and white lends a weight and obstinacy to the homoerotic scenes. There’s little ambiguity in the images. While the tone is surrealistic, the scenes are not obscured by impressionistic overlays or abstraction. There’s little ambiguity in the symbolism: The dreamers erection is a statue of a fertility God. A wrestling match is followed by a sailor lighting a cigarette with a bundle of sticks (a very literal faggot). An assault reveals the secret compass of the heart and results in the dreamer being covered in milk. A man opens his pants to reveal a roman candle. The dreamer’s partner in the end is a creature of burning light.

60 years after its making, as I watched the opening scenes — a sailor carrying the limp body of comrade or lover through a storm — the film felt as real and valid as any late-90s gay melodrama out of Hollywood. It spoke to me of my own fear of violent reprisal for my sexuality and the complications of desiring strength in men. In these images I could recognize the direction of my own heart, which I’d kept hidden for so long, and the magic inherent in waking in the morning with a love that burns almost too bright.

In 1957, a decade after being made, Fireworks was screened at the Coronet Theater (one of the first art-houses). The homosexual imagery resulted in theater owner Raymond Rohauer being arrested for obscenity. The case ultimately went to the California supreme court in a landmark decision that ruled homosexuality was a valid subject to explore through artistic expression; Fireworks could not be considered obscene.

Anger continually flaunted that particular transformative creative magic. He showed again and again that art has the ability to take what is considered obscene by broader society and turn it into a subject for meditation. In turn, that meditation can reconcile the tensions that between our lives seen as human and lives seen as taboo.

If Hollywood Babylon was a master-class in trash-culture then Fireworks was a master-class in Pride.

On May 11th of this year, Kenneth Anger died at the age 96. In his passing, I was flooded with memories from a life I’d long ago burned down to ash like those hills I once watched from my porch, smoking cigarettes and discussing music and magic with W.

He is lost to me now. And my witchy ways have been subsumed by a suburban life. But the life I once lived is still very much a part of the fabric of my being. Those threads still connect me to the mystical and the magical and the beautifully bizarre. They color my life, as bright as the Pride flag I hang on my house every June. And though I sometimes fold them away, they are still there, ready to emerge and glow in the sun — a testament to W and Crowly and Stevie Nicks and tabla-playing room mates and Kenneth Anger.

Burroughs: Naked Lunch; Starhawk: The Fifth Sacred Thing; Kerouac: Desolation Angels; Ginsberg: Howl; Spanbauer: The Man Who Fell in Love with the Moon; Lynch: Wild at Heart, Lost Highway; Joni Mitchell: Blue; Tori Amos: Boys for Pele; Stevie NIcks: Belladonna